ARCHIVAL MOMENT

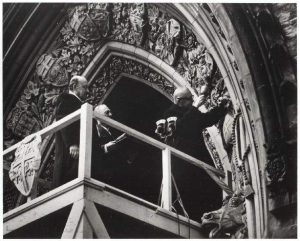

It was no secret that Archbishop Edward Patrick Roche, the leader of the Catholic Church in St. John’s during the referendum debates in Newfoundland in 1948 was strongly opposed to Newfoundland joining Confederation. He took every opportunity that he could to encourage “his people” to vote for Responsible Government.

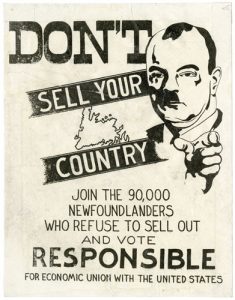

The anti-confederate forces were divided between the Responsible Government League [RGL] and the Economic Union Party [EUP]. The RGL advocated a simple return to the status Newfoundland had held in 1933. A group of younger anti-confederates formed the EUP, led by Chesley Crosbie, which promoted the idea of a special economic relationship with the United States.

In contrast, the Confederate Association under Joey Smallwood and Gordon Bradley was better funded, better organized, and had an effective island-wide network. They campaigned hard and with considerable skill and confidence.

On June 3, 1948 the results of the first referendum were released. Confederation received 64,066 votes, 41.1 percent of the total, Responsible government with 69,400 votes (44.6 percent) and Commission government was last, with 22,311 votes (14.3 percent).

On June 3, 1948 the results of the first referendum were released. Confederation received 64,066 votes, 41.1 percent of the total, Responsible government with 69,400 votes (44.6 percent) and Commission government was last, with 22,311 votes (14.3 percent).

A second referendum was set for 22 July 1948, with Commission dropped from the ballot.

Archbishop Roche was not a happy man. He looked at the results of the first referendum only to find that areas of the province that had a significant Catholic population had voted for Confederation. He was especially displeased with the people of Marystown on the Burin peninsula who had voted for Confederation with Canada. He laid the blame squarely on the shoulders of the parish priest Reverend John Fleming.

On June 26, 1948 he wrote to the Reverend Fleming:

“Words are cheap; actions speak. In the recent referendum your people of Marystown – a majority of them – aligned themselves against the rest of the Diocese. This was due largely either to your misguided leadership or to your masterly inactivity.” 200/F/2/1

Following the 22 July 1948 the Confederation option won a small majority over the Responsible Government choice, Confederation winning by 78,323 votes or 52.34 per cent over 71,344 or 47.66 per cent over the latter. Voter turnout was 84.89 per cent of the registered electors.

The Responsible Government option carried in seven districts, all on the Avalon Peninsula, and the Confederate vote carried in the remaining districts. The Confederates successfully picked up the vote previously given in the first referendum to the Commission of Government option. The same regional voting pattern evident in the first referendum was also present in the second referendum, with the Roman Catholic vote off the Avalon Peninsula having played a significant role in the Confederate vote.

Reverend John Fleming was not the only Catholic priest to advocate for Confederation. It is said that Joey Smallwood in 1964 on the death of the Reverend William Collins who had served in many parishes in Placentia Bay attended the wake service of Reverend Collins. At the service it is alleged that Smallwood said:

Reverend John Fleming was not the only Catholic priest to advocate for Confederation. It is said that Joey Smallwood in 1964 on the death of the Reverend William Collins who had served in many parishes in Placentia Bay attended the wake service of Reverend Collins. At the service it is alleged that Smallwood said:

“When I die and go to the pearly gates, I will greet St. Peter and I will ask if Father Collins is sitting on the heavenly throne , if this good Confederation supporter, this priest has not been welcomed into the heavens, I too will refuse to enter.”

On March 31, 1949, Archbishop Roche would not have been in the mood to celebrate. The act creating the new Canadian province of Newfoundland (now Newfoundland and Labrador) came into force just before midnight on March 31, 1949; ceremonies marking the occasion did not take place until April 1.

The British Parliament passed the necessary legislation on 23 March, and the Terms of Union came into effect “immediately before the expiration of the thirty-first day of March 1949” (Term 50).

With the death of Joey Smallwood in 1991 the Government of Newfoundland asked the Roman Catholic Basilica parish, where Archbishop Roche is buried in the crypt, if they would host the funeral for the former premier. The Basilica parish agreed. It was the first time that the two were in the same building. The choir director (Sister Kathrine Bellamy, RSM ) said to one of the choir members, “Would you go down into the crypt and sit on Archbishop Roche’s coffin, for surely he is spinning in his grave that they have allowed Joey in his church.”

Recommended Exhibit: Future Possible: Art of Newfoundland and Labrador from 1949 to Present: Taking place on the 70th anniversary of Confederation with Canada, this exhibition gathers close to 100 artworks, images and objects from across The Rooms art gallery, archives and museum collections to ask questions about how histories are told and re-told. The exhibition examines the period after Confederation in 1949, placing historical works in conversation with works by contemporary artists. The exhibition will be accompanied in Fall 2019 by a major publication that marks the first comprehensive art history of the province.

Recommended Website: The 1948 Referendums: http://www.heritage.nf.ca/law/referendums.html