ARCHIVAL MOMENT

December 27, 1862

In Newfoundland the tradition of mummering or jannying (December 26 – January 6) is often associated with the mummer’s parade, home visitation, music and the occasional drink! The tradition has a darker side.

Few people know that in order to mummer in Newfoundland participants at one time needed a license to do so and that for almost 100 years mummering was outlawed!!

In the tradition of mummering, friends and neighbours conceal their identities by adopting various disguises, covering their faces, and by modifying their speech, posture and behavior.

It was not surprising that some, using these disguises, would be up to no good. Some in disguise would use the mummering season to retaliate against those that they disliked or had some grudge to settle.

In order to control mummering and the violence associated with it in June 1861, the Newfoundland government passed an act which dictated that:

“any Person who shall be found… without a written Licence from a Magistrate, dressed as a Mummer, masked, or otherwise disguised, shall be deemed guilty of a Public Nuisance”. Offenders were to pay “a Fine not exceeding Twenty Shillings”, or to serve a maximum of seven days’ imprisonment (Consolidated Acts of Newfoundland, 1861: 10).

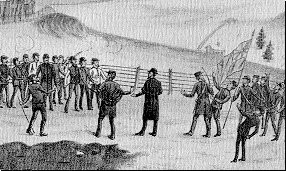

On December 27, 1862 in the Town of Harbour Grace, Constable Joseph Nichols arrested and dragged before the local magistrate, Joseph Pynn and a few of his friends, Constable Nichols told the court:

“they had veils over their faces and was disguised in female clothing and the other in men’s dress, they were acting in all respects as mummers.”

The magistrate was not amused, Jospeh Pynn was “fined each 20 pounds sterling or 7 days imprisonment.” Pynn and his friends were not about to spend Christmas in jail – the court record shows that “Stephen Andrews paid the fine and all discharged.”

The idea of a license to mummer did not go over very well. Mummering was a passion ingrained in the culture of the Newfoundland people. The St. John’s newspaper the Public Ledger in January 1862 suggested that 150 licenses had been issued during the preceding Christmas season, but that many more participants in the custom had failed to comply with the new legislation.

Recommended Archival Collection: The Rooms Provincial Archives: GN5 /3B/19 Box13, File Number 3

Recommended Reading: Any Mummers ’Lowed In? Christmas Mummering Traditions in Newfoundland and Labrador. Flanker Press, St. John’s, NL. 2014. Folklorist Dale Jarvis traces the history of the custom in Newfoundland and Labrador and charts the mummer’s path through periods of decline and revival. Using archival records, historic photographs, oral histories, and personal interviews with those who have kept the tradition alive, he tells the story of the jannies themselves.

The Rooms is dressed for Christmas – come take a look at our Christmas trees! We have a special “mummers tree”.