ARCHIVAL MOMENT

April 15, 1890

Petition to establish public baths in St. John’s

An “outport visitor” to St. John’s in April 1890 was quite shocked to hear that it was the “intention of some young men of St. John’s to petition the government to establish public baths.” The ‘outport visitor’ was so troubled that he penned a letter to the Editor of the St. John’s newspaper the Evening Telegram making his objections known.

The ‘outport visitor’ wrote to the newspaper that he saw “the necessity of the baths” but “to ask the Government to establish them is something beyond human imprudence, and I should be surprised to find the people of St. John’s backing up such a proposal.”

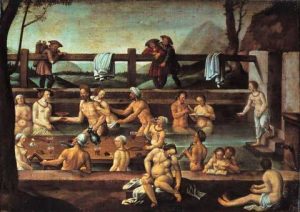

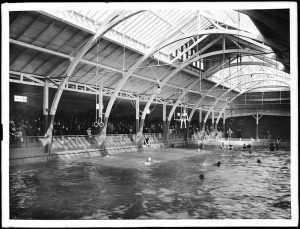

At the time a ‘bath house’ was essentially a large room with rain showers and a plunge pool with a large swimming pool.

The idea of ‘public baths’, at this time, was a concept that was taking hold in many cities in North America. Most homes did not have indoor toilet facilities or any kind of bath facilities. The young men of St. John’s were aware that in United States, there was a progressive move for cities to build public baths. Some cities in North America saw the idea of ‘public baths’ as a ‘moral imperative’ a Brooklyn, New York newspaper editor wrote :

“… it is a duty of the public, as its own government, to educate [the poor] out of their condition, to give baths to them that they may be fit to associate together and with others without offense and without danger. A man cannot truly respect himself who is dirty. Stimulate the habit of cleanliness and we increase the safety of our cities. And give over the idea that a free bath is any more of a “gratuity” than the right to walk in the public streets.”

In Newfoundland the “outport visitor” had little time for such considerations. He argued if the:

‘public baths’ were approved next you would have “the young men petitioning the Government to provide them with soap and towels for their daily ablution… I should have thought that there was enough of private enterprise in St. John’s to start baths, where each person might obtain admittance on payment of a penny or so for each occasion. But if this cannot be done, let these young men apply to Municipal Council to give them baths.”

The letter continued; if the young men of St. John’s can have a bath house at the expense of the taxpayers why not the men of Twillingate, Bonavista, Trinity, Harbour Grace and Placentia. He concluded, it would be an injustice to establish a ‘bath house’ in St. John’s at the expense of the tax payers.

It was all too much for the ‘outport visitor’; he concluded that if ‘municipal officials’ could consider luxuries like ‘bath houses’ for their young men of St. John’s, then they were getting too much money from the Government. He wrote: “St. John’s has been the petted child of every Government and the people of St. John’s are spoiled.”

The ‘outport visitor’ who wrote the letter to the editor was not aware that St. John’s had a long tradition of supporting ‘bath houses’. The “Princess Bath” on Water Street was advertising that it was open to the public as early as July 1860. The advertisement for the Princess Bath read:

“The public of Newfoundland, visitors and travellers, are informed that the town of St. John’s is at length supplied with … Hot, Cold, Vapor and Shower, Salt and Fresh Water BATHS: also Salt Water Swimming BATHS …[with] separate departments for Ladies and Gentleman – and is situated on Water Street near the Galway Steamship Company’s Wharf. Open from 6 am – 9 pm summer and 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Winter and from 3 – 6 p.m. on Sundays. A female superintends the ladies department.”

With the introduction of indoor plumbing and bathing facilities in the home ‘public baths’ were gradually replaced by the more conventional swimming pools.

Recommended Archival Collection: A great place to discover history is in the pages of our local newsappers. Take some time to explore the newspaper collections in your city or town. From your desktop take some time to explore Memorial University’s Digital Archives Initiative (DAI), your gateway to the learning and research-based cultural resources. The DAI hosts a variety of collections which together reinforce the importance of the past and present, of Newfoundland and Labrador’s history and culture. Read More: http://collections.mun.ca/

Recommended Reading: Washing “the Great Unwashed” Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920 (Urban Life and Urban Landscape Series) Ohio State University, 1991