December 7, 1884

“A derelict schooner, drifted ashore at St. Bride’s … “

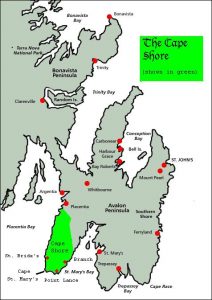

As Christmas 1884 approached, the people of St. Bride’s, Placentia Bay, were thinking it would not be a prosperous Christmas. It had been a poor year in the fishery. Their fortune was however about to change unhappily born on the pain of other families from Placentia Bay.

As Christmas 1884 approached, the people of St. Bride’s, Placentia Bay, were thinking it would not be a prosperous Christmas. It had been a poor year in the fishery. Their fortune was however about to change unhappily born on the pain of other families from Placentia Bay.

On December 7, 1884 residents of St. Bride’s stood on ‘the bank’ overlooking Placentia Bay watching as a “a derelict schooner, drifted ashore at St. Bride’s, dismasted and waterlogged…”

There was much excitement in St. Bride’s, it was quickly realized that “Sixty three barrels of flour and six puncheons of molasses” was aboard the vessel. It was theirs to salvage, they would take it home.

In the days following the salvage effort, St. Bride’s fell silent. James E. Croucher, the Wreck Commissioner stationed at Great Placentia had arrived in the town on December 10. He immediately began a search for the cargo of the ill-fated schooner, but to his dismay only found “24 barrels of flour broken and in a damaged condition, and two puncheons of molasses …”

Thirty nine (39) barrels of flour and four (4) puncheons of molasses were not accounted for.

Croucher, as the Wreck Commissioner was obliged by law, under the Consolidated States of Newfoundland to travel to St. Bride’s to investigate the loss of the Schooner, he could only conclude: “the remainder of the property being distributed amongst salvors by a person or parties who had no authority from me to do so.”

As he sailed out of St. Bride’s for Great Placentia the residents of St. Bride’s no doubt celebrated. With their newly acquired abundance of flour and molasses, it would be a good Christmas.

The people of St. Bride’s also mourned, they knew that their gain came at the loss of the crew of the Schooner Stella, a crew of nine men out of nearby Oderin, Placentia Bay. It is said that she was wrecked in the “terrific gale of November 1884.”

Ever respectful of the dead, it is reported that “All the clothes that had belonged to the lost men that had been taken from the Schooner were carefully dried and forwarded to their families.”

The 1874 census listed a population of 140 in 29 families. Thirteen residents were from Ireland and one from Scotland. The 79 fishermen had 22 boats. The 13 farmers had 203 cattle, 30 horses, 139 sheep and 113 swine on 200 acres of land. Products included 60 bushels of oats and 5,460 lbs. 01 butter

By 1891, the population had increased to 256, including four from Ireland. The 66 fishermen-farmers. The community also had a priest, a teacher and a merchant, and 65 of the 122 children were in school.

What about the name?

The name of St. Bride’s is quite modern, and was given from the titular Saint of the Church of St. Bridgett.

The name of St. Bride’s is quite modern, and was given from the titular Saint of the Church of St. Bridgett.

On more ancient maps it (St. Bride’s) was called La Stress, apparently a French name which became corrupted into Distress.

This name “Distress” in 1876 was reported by the newly arrived priest Reverend Charles Irvin as “not being of pleasant sound” and having the authority of the church the priest changed the name from Distress to St. Bride’s .

Recommended Archival Collection: The Maritime History Archive, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. Johns, holds 70% of the Crew Agreements from 1863-1938, and 80% of the Agreements from 1951-1976. The crew agreements include particulars of each member of the crew, including name (signature), age, place of birth, previous ship, place and date of signing, capacity and particulars of discharge (end of voyage, desertion, sickness, death, never joined etc). http://www.mun.ca/mha/

Recommended Exhibit: At the Rooms: Here, We Made a Home: At the eastern edge of the continent, bounded by the sea, the culture of Newfoundland and Labrador’s livyers was tied to the fisheries and the North Atlantic. A rich mix of dialects, ways of life, food traditions, story and song developed here. The Elinor Gill Ratcliffe Gallery – Level 4