ARCHIVAL MOMENT

April 14, 1912

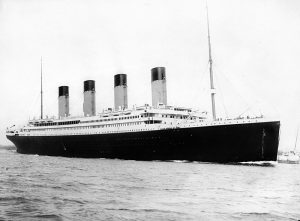

On April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic set sail from Southampton on her maiden voyage to New York. At that time, she was the largest and most luxurious ship ever built. At 11:40 PM on April 14, 1912, she struck an iceberg about 400 miles off Newfoundland. Although her crew had been warned about icebergs several times that evening by other ships navigating through that region, she was traveling at near top speed of about 20.5 knots when one grazed her side.

On April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic set sail from Southampton on her maiden voyage to New York. At that time, she was the largest and most luxurious ship ever built. At 11:40 PM on April 14, 1912, she struck an iceberg about 400 miles off Newfoundland. Although her crew had been warned about icebergs several times that evening by other ships navigating through that region, she was traveling at near top speed of about 20.5 knots when one grazed her side.

In 1912, the Marconi wireless radio was still in its infancy state as far as utilization. Marconi operators, Harold Bride and Jack Philips on the direction of the ships Captain (Smith) put on the headphones and immediately began tapping out CQD – MGY … CQD – MGY which translates to CQD = Come Quick Danger or attention all stations, D = distress or danger, and MGY was the Titanic’s radio call letters.

Walter Gray, Jack Goodwin and Robert Hunston were serving at the Marconi Company wireless station at Cape Race, Newfounldand 400 miles west of Titanic. The wireless news was being handled by them.

TWO FRIENDS: THEIR LAST CONVERSATION

TWO FRIENDS: THEIR LAST CONVERSATION

It would have been a very difficult night for Walter Gray at Cape Race. The Marconi operator on the Titanic was his good friend Jack Philips. Jack had been the last person that he had seen in England before he had departed for Newfoundland. Walter had been excited all the day of April 14 – he was waiting anxiously at Cape Race waiting for the Titanic and his good friend Jack to come within ‘hearing” distance of Cape Race. Walter later wrote:

“That evening I held brief conversation with Philips. He emphasized the magnificence of the vessel, the wonderful group of passengers and the good time being had by all.

Later in the evening the second operator (Hunston) called out “Mr. Gray the Titanic has struck an iceberg and is calling C.Q.D. (COME QUICK DANGER) I immediately dropped what I was doing and ran to the operating room.

Donning the headphones, I heard Philips call for help using both distress calls, C.Q.D. and the newly-introduced S.O.S. His call included the ship’s position in Latitude and longitude, weather conditions, and the story of striking the berg. When he ceased, I called the Titanic and inquired whether I could assist in any way. Philips thanked me and asked me to stand by.

A short time after 2:00 a.m. a very weak distorted signal was heard and the “Virginian” being much closer picked up what they thought was Philips voice trying to get a message out and that was the last word from the radio operator, Philips.”

Less than three hours later, the Titanic plunged to the bottom of the sea, taking more than 1500 people with her. Only a fraction of her passengers were saved. The world was stunned to learn of the fate of the unsinkable Titanic.

Water Gray’s good friend Jack Philips was one of those that perished.

Questions raised by the Titanic tragedy

In response to the questions raised by the Titanic tragedy, a conference was held attended by representatives from 13 nations. Out of that came SOLAS, a comprehensive set of regulations outlining safety protocols at sea. The International Maritime Organization was established in 1948 by the United Nations as the agency responsible for the safety and security of shipping.

Every year, a flight heads out over the waters off Newfoundland. When it reaches the site of the remains of the Titanic, the back of the C-130 aircraft is opened and a crewmember throws a wreath on the water, commemorating those who lost their lives when the ship went down.

The patrol monitors ice and icebergs off the Grand Banks and provides the ice limit to the shipping community. According to the U.S. Coast Guard, “No vessel that has heeded the Ice Patrol’s published iceberg limit has collided with an iceberg.”

Recommended Archival Collection: At the Rooms Provincial Archives Division: The Cape Race Log Book: A journal of predominantly one line entries highlighting events of local, national and international interest, as maintained by various members of the Myrick family at Cape Race and Trepassey. Includes reference to the sinking of the Titanic.

Recommended Exhibit: At the Rooms see the life vest worn by James McGrady his body was recovered by a Newfoundland vessel the Algerine and the body was then transferred to another Newfoundland ship, the SS Florizel. The Florizel took the body to Halifax for burial in Fairview Lawn Cemetery.

Recommended Exhibit: At the Rooms see the life vest worn by James McGrady his body was recovered by a Newfoundland vessel the Algerine and the body was then transferred to another Newfoundland ship, the SS Florizel. The Florizel took the body to Halifax for burial in Fairview Lawn Cemetery.

Recommended to view: http://www.cbc.ca/nl/features/titanic/