Archival Moment

March 31, 1914

In 1911, Reuben Crewe was one of a handful of sealers who swam to safety when their vessel sank in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Afterwards Reuben’s wife, Mary, insisted that he give up sealing. She could no longer bear the sleepless nights of worry for his safety.

In 1911, Reuben Crewe was one of a handful of sealers who swam to safety when their vessel sank in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Afterwards Reuben’s wife, Mary, insisted that he give up sealing. She could no longer bear the sleepless nights of worry for his safety.

It was a rite of passage for the young men of Newfoundland to try and find a berth on one of the sealing vessels going to the ice to prosecute the seal fishery. In March 1914, Albert John Crewe had just turned 16 and he was determined that he was going to go.

His mother refused to listen to her young son. The boy insisted, he was determined go. Finally she relented but she insisted he would only go if his father took him under his wing.

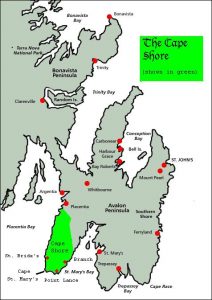

Ruben Crewe agreed. He and his son signed up on the S.S. Newfoundland with a group of other men from Elliston on March 4, 1914.

On March 30th, 1914, Ruben and his son John Albert with another 164 men left the SS Newfoundland and headed towards the SS Stephano seven miles away. For the next two days they were lost in a vicious blizzard; the captain of each ship assuming the men had found refuge on the other. 78 men were to freeze to death, including Ruben and Albert.

Cassie Brown in her book ‘Death on The Ice’ wrote about the father and son. They had struggled for hours to stay alive, the father encouraging his son to walk to move.

“But now, father and son were unable to encourage each other any further. Albert lay on the ice to die, and his father lay beside him, drawing his son’s head up under his fishermen’s guernsey in a last gesture of protection. They clasped in each other arms, they died together.”

Rescuers from the S.S. Bellaventure found Reuben and Albert John frozen in an embrace, the father attempting to shield his teenage son from the elements.

Mary, the wife and mother, recounted later that she was awakened the night of the disaster to see Reuben and Albert John kneeling at her bed and that she was struck by the look of peace on their faces.

The embrace of father and son has been immortalized in a statue that was created by renowned bronze sculptor and visual artist Morgan MacDonald. The statue was erected in Elliston, Newfoundland commemorating those lost in the tragedy.

Recommended Archival Collection: At the Rooms Provincial Archives see GN 121 this collection consists of the evidence taken before the Commission of Enquiry regarding the S.S. Newfoundland. The collection includes the Sealers Crew Agreement and the evidence given by the surviving members of the crew. Evidence entered concerning the loss of the SS Southern Cross is also included on this collection.

Recommended Film: The National Film Board’s documentary 54 Hours written by Michael Crummey, uses animation, survivor testimony and archival footage to create the story of the Newfoundland Sealing Disaster. View this short film from your own home at https://www.nfb.ca/film/54_hours

Crew List: In the days and months following the loss of the S.S. Southern Cross and the tragedy of the loss of the men of the S.S. Newfoundland there was much confusion about the names and the number of men that did die. You will find the definitive list of all those that did die as well as the survivors at http://www.homefromthesea.ca/

Recommended Reading: PERISHED by Jenny Higgins (2014) offers a unique, illustrative look at the 1914 sealing disaster through pull-out facsimile archival documents.