Archival Moment

November 28, 1894

In late November of 1894 a young clerical student challenged the Editor of the local St. John’s newspaper the Evening Telegram to encourage a debate about the merits of dancing. The young clerical student wrote:

In late November of 1894 a young clerical student challenged the Editor of the local St. John’s newspaper the Evening Telegram to encourage a debate about the merits of dancing. The young clerical student wrote:

“I want to know whether it is right or wrong, and perhaps if a discussion on the subject were opened up, one would be better able to judge.”

A number of subscribers to the Evening Telegram took on the challenge and penned letters making their positions known and they had very definite opinions.

Elizabeth A. Nyle from her home on Freshwater Road, St. John’s was the first to enter the fray stating quiet categorically that she was quite opposed to dancing. She wrote:

“It (dancing) involves extravagance of dress, and too often a shocking indelicacy of dress likewise. It involves contacts and caresses of young men and women which stimulate sensual passions. It kindles salacious thoughts. An evening spent in that way is not a recreation, it is a “revealing,” and ministers to vanity, frivolity, jealously and fleshy lusts , which war against the soul.”

Other letters to the Editor supported the notion of dancing. One woman writing under the pen name Minerva (the Roman goddess of wisdom and sponsor of arts) wrote:

“I should certainly say that there can be no possible harm in this innocent pastime, as dancing is one of the most pleasant ways of taking exercise. It suits all classes, old and young, the old folks almost becoming young again under its vigorous influence. … It certainly is the great key to social intercourse, unbending even the most rigid in their endeavor to keep up with the music.”

If you were to go out dancing in St. John’s in the 1890’s the two most popular dances were the ‘Valse” and the “Minuet.”

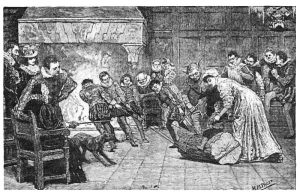

The “Valse” was a relatively new dance in St. John’s and in 1894 considered “the dance”, but it seems “very few people knew how to dance it well.” Today we know the “Valse” as the Waltz . When first introduced into the ballrooms of the world in the early years of the Nineteenth Century, it was met with outraged indignation, for it was the first dance where the couple danced in a modified Closed Position – with the man’s hand around the waist of the lady.

The “Minuet” was also very popular at the time it was described as “being very graceful and when seen from a distance looks very imposing.”

In November 1894 all of the “Assembly Halls” in St. John’s were actively advertising for the “dancing season.” The West End Amusement Club was offering “dancing assembly’ every Wednesday night. The British Hall offered “dancing assembly” every Thursday night.

In St. John’s, “Christmas dancing was the chief amusement ; in fact it is the “dancing season” when old and young alike join in the sport, making old Father Xmas glad he came once more.”

It is likely that Mrs. Elizabeth A. Nyle was not amused.

My dance card is full.

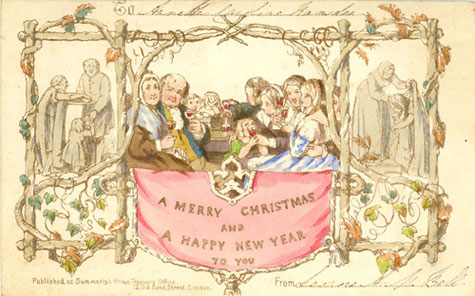

A dance card is a card that was provided at large balls and dances with a list of the dances for the evening with a space beside it. The ladies would each have a card, sometimes with a small attached pencil, and when a gentleman asked her to dance, he would write his name in for a particular agreed upon dance. This was to help the lady remember who she agreed to dance with and to avoid the embarrassing situation of promising to dance the same dance with two different men.

Credit: The Rooms; St. John’s, NL

Title: Dance Card for event at Government House, 1939 MG 373.5