Archival Moment

May 14, 1918

On May 14, 1918, Mr. Frederick Harris of Glovertown, Bonavista Bay received in the post a package that read:

“one package of effects, which belonged to your son, the late #2607 Private Eugene Harris of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment.”

Twenty (20) year old Eugene had died in action in the trenches of France a few months earlier.

The package contained “one identity disc and one cigarette case.”

The package was also supposed to include a pair of seal skinned boots that the father had sent to his son but the father upon hearing that his son had died wrote to the war office and suggested:

“I would like you to sell the skin boots and give the money toward the keep of the soldier’s graves in France, the socks and mits I would like to be sent to my other son No. 3365 Private Clarence Harris in France. I don’t suppose he will need the boots as I sent him a pair when I sent the other dear boy the boots … “

When he was writing the letter Frederick Harris was not aware that his other son Clarence had also died. News had not yet reached the family.

Two of his sons lay dead in the trenches of France.

The Harris family like thousands of other families in Newfoundland upon hearing of the death of their sons were determined that if their child was to be buried in foreign soil that the grave be a respectable plot and well maintained. It was the prayer of this grieving father that the sale of the seal skinned boots would help in some small way to offer this dignity.

Five years following the death of his two sons Frederick Harris writing to the war office asked for a photo of the graves where his sons were buried. With photo in hand he wrote:

“I received the photos of the grave of my boy Eugene Harris. Thanks very much.”

The only remembrance that the families had of their “soldier boys” was a photo of the grave that was hung in an honored place in the household and the few contents of the package of effects that was sent to them.

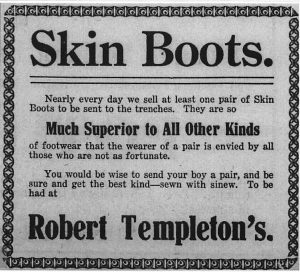

The men of the Newfoundland Regiment that fought in the trenches of France in the Great War suffered prolonged exposure of the feet to damp, unsanitary, and cold conditions that often lead to ‘trench foot.’ It was not unusual for young soldiers like Eugene Harris to write home and order ‘seal skinned boots’ that offered the best possible protection against the wet and cold.

The sale of Private Eugene Harris’s pair of seal skinned boots at the request of his father was one of the many acts of generosity shown by Newfoundlanders that would eventually see the erection of memorials in France and communities throughout Newfoundland and Labrador.

Recommended Archival Collection: Over 6000 men enlisted in the Newfoundland Regiment during the First World War. Each soldier had his own story. Some soldiers’ stories were very short; other soldiers who were lucky enough to survive the war had a longer story to tell. Each story is compelling. Read More: https://www.therooms.ca/thegreatwar/in-depth/military-service-files/database

Recommended Museum Exhibit: Beaumont Hamel: The trail of the Caribou: The First World War had a profound impact on Newfoundland and Labrador. Our “Great War” happened in the trenches and on the ocean, in the legislature and in the shops, by firesides and bedsides. This exhibition shares the thoughts, hopes, fears, and sacrifices of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians who experienced those tumultuous years – through their treasured mementoes, their writings and their memories. https://www.therooms.ca/exhibits/now/beaumont-hamel-and-the-trail-of-the-caribou